Quiet, even subdued, cautious, the Neal Martin on my screen is quite different to the garrulous character I’d imagined from his writing. On the page (or more often these days, the screen), Martin pokes fun at the wine industry, his articles often opening with satirical fiction that doesn’t hold back.

His reports and tasting notes are littered with music references (think Primal Scream and The Smiths rather than Wagner and Bach), and mentions that are sometimes pointedly popular – his first Bordeaux en primeur report for the Wine Advocate (taking over from Robert Parker) opened with a line from Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. On our call, however, each word feels deliberate and considered, confident, but with a definite wariness that doesn’t quite fade.

Aged 50, the Vinous writer’s trajectory to wine stardom is unusual. Born in Essex, Martin grew up in a household that didn’t drink wine, so nor did he. In fact, he had no interest in it and blagged his way into the industry. In 1996, having lived in Japan, he applied for a role sourcing wines for a subsidiary of Japan Airlines: the only hitch that he didn’t know anything about wine at the time.

“I lied my way through the interview. I went to an off-licence the night before. Memorised some of the labels. I just reeled off a couple of names… [they] thought I was into wine and gave me the job,” he tells me, still rather bemused by their decision. Coincidentally Martin returned to the same shop last year, where unbeknown to him, his tale lives on as local offy legend – the famous wine taster that got his start right there in Leigh-on-Sea (with the owners even deeming him worthy of several selfies).

Unashamedly a terrible employee, he spent much of his time in his role for Japan Airlines starting his wine writing career (although it also sounds like there was a fair amount of lunching too). “I was kind of bored one lunchtime, bought a book on computer coding. I found I could make a webpage, and just kind of built the original wine-journal.com when I should have been working,” he says. From the novelty of creating a site, he started writing his own tasting notes. At that time the great wine writers were Michael Broadbent, Steven Spurrier and Hugh Johnson – English gentlemen, in short; charming, wonderful, but – for many – unrelatable, very “high culture”, as Martin puts it. He set out to be “more down-to-earth, funny, irreverent”.

“At the time, there was nobody else really doing that. There was this huge audience that liked to drink Bordeaux – but also liked Radiohead.” It struck a chord – and soon his self-built site was getting over 500,000 hits per month. No wonder therefore that in 2006 Robert Parker – then still at the height of his fame – approached the music-minded Englishman to join the Wine Advocate team.

Of course, Parker was renowned for not just the power of his palate and revolutionary points system, but for his personal tastes. Many argue that his preference for intensely ripe, high-octane, new-oak-aged styles shifted the entire world of wine – pushing producers to craft wines that would earn his favour. “Especially more to the end of his career, he had a certain palate… but people always forget that he reviewed German wines and Alsace and so on. So it becomes a little bit of a cliché,” Martin says of his once mentor.

The world of flavour is undeniably subjective, yet Parker was – by some – damned for just that, daring to express his personal preference. Total impartiality when it comes to the matter of taste seems impossible. After I ask whether or not he feels there’s room for bias in wine writing, Martin is clear: “I think a critic should stand up for what they believe in. Anyone can say the First Growths are great, DRC is great. I’d rather read someone who has a definite view on something, whether they like natural wines, or orange wines. Stand up for what you believe in. Then it’s up to the reader to decide.”

In fact, he goes as far to say, it’s potentially the lack of difference in views that has led to wine criticism becoming “a bit beige” in recent years – because now it’s a career, something upon which people depend for their livelihood. “It’s more of a risk if you say this famous name didn’t produce a great wine,” Martin notes.

The danger of losing access to wines that are far beyond most critics’ budgets is a threat to the independence of wine writing, but also a massive obstacle to new voices in the industry. It’s an especial challenge given many of the wines Martin reviews – in particular older vintages – might only be pulled out at private dinners, hosted in producers’ homes. The very nature of wine – limited in production and fleeting in its consumption – leads to a reliance on the hospitality of its makers. Martin argues that for that exact reason the most independent “critics” are arguably those he describes as the “grands amateurs” – those who can afford to buy the world’s finest wines, and therefore say what they want.

Martin, however, feels there’s a line to be found where he can maintain distance yet be friendly – and, importantly, speak freely. He highlights Laurent Ponsot’s 2015s – which he gave relatively scathing scores – but, having known Laurent for many years, Martin was happy to tell the vigneron outright that he thought they were picked too late.

As for Martin, he had a lucky start with access to unbelievable wines in what he deems a “golden era” for fine wine in the 1990s, when top Burgundy and First Growths remained affordable for the many – and were poured freely by the trade. “I’ve never taken that for granted. Some of the wines I drink… they’re what my friends earn in three or four months. I never drink a wine and I’m blasé about it. But I’ve been around long enough to say what I think.”

Preserving his voice has always been of key importance to Martin – not willing to compromise on keeping his distinctively tongue-in-cheek tone, but also offer something more than just a tasting note. “When I joined Parker, it was an easy decision – he was a kind of god. But at the same time I wanted to make sure I could still write in the way I wrote,” he tells me. “Anyone can taste the wines and add a number, but for me it’s more interesting to create something that’s interesting, gives you insight… that’s the challenge: to write something people don’t expect,” Martin says. Does he feel he’s achieving that? His answer: “When my primeur report comes out, read the first three paragraphs and let me know.” [We spoke at the end of April, just before the report was published.]

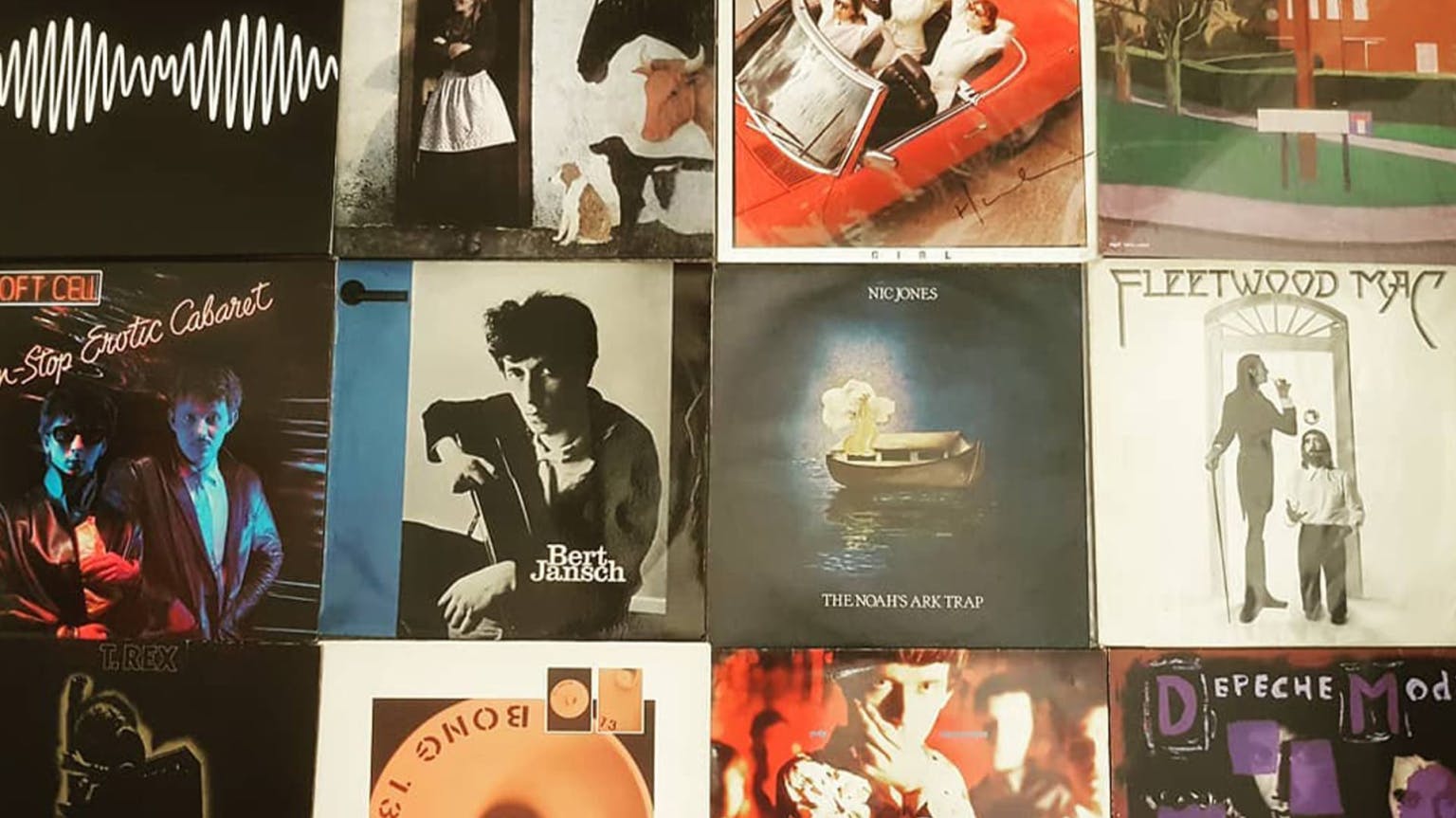

For Martin, his love of music is integral to his work. Indeed, it seems that way – the record player and stacks of vinyl visible behind him on our Zoom call, his Instagram feed almost equally split between sleeve covers and labels – and he feels that it makes him a better writer. He looks back to Hugh Johnson (an avid gardener) or Michael Broadbent (pianist and art enthusiast) for precedent. “Wine can be a boring subject – but it’s when you put it with other things that it becomes more interesting,” he says.

Case in point is his recent article on Grand Mayne, he tells me: “It’s more about time, and parenthood, and… kind of sad in a way. To me, that’s the kind of counterbalance to the dryness about wine. It smells of strawberries and it’s 92 points. There’s the other side to the story – that’s the harder part to write, but for me it’s more satisfying.”

Indeed, he even self-published his book Pomerol (in 2012) to avoid the unwelcome interference of editors. In 2017, Martin made the leap to Vinous – joining fellow Wine Advocate alumnus Antonio Galloni’s new venture, and while he’s kept his voice, he’s also had to learn how to be edited “which was… quite a challenge for me at first,” he admits. “But actually now it’s something I really needed. I think they make better articles, it makes me think a bit more about writing.”

There have been a lot of bottles over the years (Vinous alone holds over 21,000 of his tasting notes), but it was a bottle of 1982 Montrose that started everything. “It wasn’t the best wine I’ve ever had by a long way… It’s a disappointing 1982,” he says. “Enjoy with modest expectations” reads his note from 2017 (88 points – upgraded to 91 points at his most recent tasting in 2018). Disappointing it may be, but it’s the bottle that made him sit up and take wine seriously, realising why people obsessed over it – although he’s clear that, for him, wine isn’t everything.

“Wine is my job – if it didn’t pay I couldn’t do it. I love wine, but I don’t think I’m obsessed with it. I don’t drink wine every day, and it doesn’t bother me if I don’t. If you think wine is everything, you’re missing something,” he says, frankly. I wonder how much this perspective has been shaped by Martin’s quadruple bypass surgery two years ago – a skirmish with the other side that has forced a visibly drastic lifestyle change, and about which he has been vocal.

In Martin’s own words, it’s a “bizarre set of circumstances” that set him on his wine-lined path, yet here he is, his pen and palate working in combination to make him one of the world’s most influential wine writers. While the golden era that allowed him to enter the industry might be over, he feels that – despite now being “very, very expensive” – in some ways wine is more accessible than ever.

“I meet so many more people from so many walks of life. I love it when you sit around the table and everyone’s from different countries. But as soon as you put a wine in front of them – everyone’s on the same level.” While one can’t argue that Martin champions the “everyman” reviewing the world’s finest wines, it’s remarkable in many ways that he hasn’t erred from his original purpose. Though the Essex-born critic doesn’t seem comfortable under the spotlight, on the page he’s at ease – free to fight against the pomposity of wine, with an irreverence and knowing self-ridicule that has put him front and centre in the industry – whether he likes it or not.